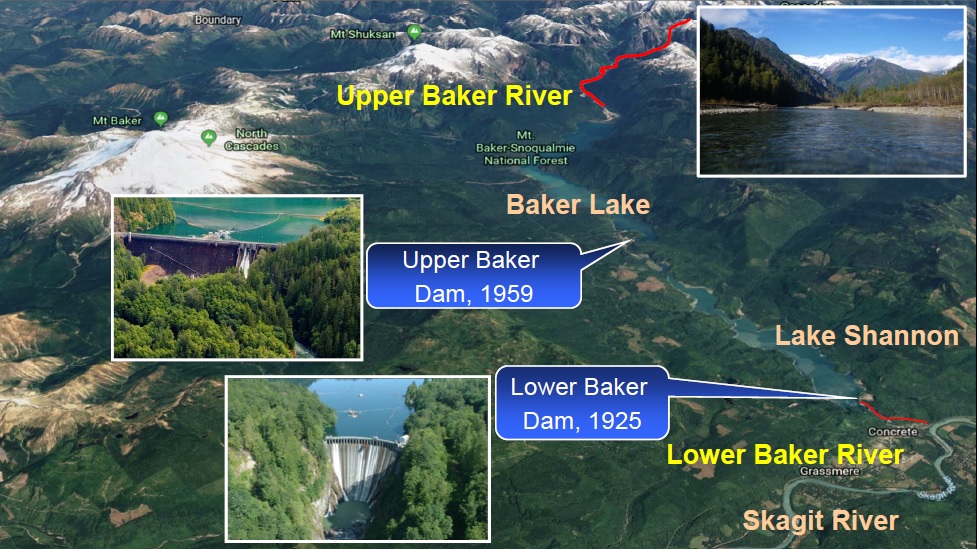

Amid the shadow of Mount Baker and surrounding natural beauty, The Baker River Hydroelectric Project is Puget Sound Energy’s largest hydropower operation. Its two dams, which help form the reservoirs of Baker Lake and Lake Shannon, produce 215-megawatts of power.

But as a major tributary of the Skagit River, the Baker River is also a critical route for migratory fish species like sockeye and Coho salmon. In the mid-1980s, declining fish populations had reached critically-low numbers, but in the ensuing decades, PSE’s investment in fishery systems has brought those populations back from the brink.

PSE’s greatest gains in helping local fish populations have come since 2008, when the company received a new 50-year federal operating license for the Baker River Hydroelectric Project. Since then, PSE has worked collaboratively with 23 different agencies at the local, state, federal and tribal levels to create and operate a number of fish enhancement facilities and processes.

The Life of a Salmon

The Baker River Basin is home not just to sockeye and Coho salmon, but also to cutthroat and bull trout, among other species. But sockeye remains its most plentiful variety.

The life cycle of this fish, of course, is one of upstream and downstream migration, beginning each autumn with eggs laid in fresh water spawning grounds. Those eggs hatch about three months later, and after feeding off egg yolk sacs for several weeks, the young fish, known as fry, learn to swim.

The fish continue to grow, and are known as parr until their first birthdays, by which time they become smolt. At this stage, known as smoltification, the juvenile fish head downstream towards a salt water environment. After several years in the Pacific Ocean, the adult salmon head back upstream into fresh water, back to the Baker River, with that activity peaking in the summer months.

Upon reaching spawning grounds, the fish will spawn by October and then die within two weeks of completing their life cycle.

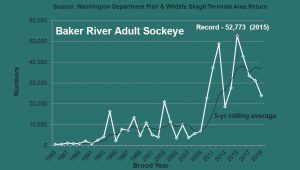

For many decades along the Baker River, adult sockeye returns averaged 3,500 fish. But by 1985, that return had bottomed out at just 99 fish. Arnie Aspelund, senior resource scientist at PSE, says that double-digit number was a wake-up call for PSE and everyone involved in monitoring fish migration.

At that point, PSE fish restoration efforts began in earnest, with 8 of the 10 highest annual returns on record occurring since 1994. In 2015, a record number of 52,773 sockeye salmon returned to spawn. Juvenile sockeye populations set a fish passage record two years later, registering nearly 1.1 million smolt. Records continue to be set this year, when salmon fry production at the Sockeye Population Enhancement Facility hit 11 million.

How It Works

The Baker River’s dams are too high for fish ladders, so trapping and hauling the fish must be done instead.

One of the ways PSE has vastly improved fish populations through this method is with Floating Service Collectors (FSCs) at both dam sites. These fish passage facilities are set up on the reservoir side of the each dam, and consist of shore-to-shore, surface-to-lakebed mesh guide nets covering five acres of surface area. The nets are linked by a 130-foot-by-60-foot barge-like structure on the reservoir surface.

When juvenile fish swim downstream into the FSCs, they are trapped. The fish are then routed to a fish sampling station for evaluation by scientists, before being loaded into water-holding trucks that will drive 20 to 30 minutes downstream past the dams, before being re-released into the river.

“These initiatives are really shining as the current standard for this kind of passageway,” says Aspelund, who adds that their FSCs have achieved international interest because of their success.

In addition to FSCs, a 2010-built upstream fish trap at the Lower Baker Dam provides state-of-the-art capture and transport of returning salmonids. An aquatic elevator raises the captured fish from river level to an elevated trap facility. Next, a programmable control system and operator’s booth allows sorting of fish by species, entering each type of fish into specific holding pools.

The fish are then sampled with electronic data equipment to collect biological information, before being carried around the dams in specialized trucks. Each truck carries the slogan “Carrying Salmon Home to Conserve a Natural Resource” on its side.

Other facilities include the 2010-built Baker fish hatchery, which vastly outpaces the previous hatchery’s annual fry producing abilities. In addition to egg incubation trays and rearing tanks, the hatchery also features several man-made spawning beaches for the fish to naturally spawn. These consist of gravel-bottom pools fed by percolating spring water. At the second Lower Baker Dam, a new powerhouse allows for better river-flow control and downstream habitat protection.

All in all, the ever-continuing work of these PSE fish facilities are ensuring a healthy and growing population of sockeye and other fish species for decades to come.

“Everyone at Puget who has worked on this has a huge amount of pride and gratitude towards how things have worked out,” Aspelund says. “To see a fish run that was on the brink of extinction come back to the way it is now, is a testament to the dedication, perseverance, and collaborations that have allowed significant gains in the river’s fish stocks.”

Sponsored