The western U.S. has seen its share of boomtowns come and go. They flourished where adventurers sought to make a buck off natural resources—such as gold, silver and lumber—and where entrepreneurs sought to make a buck off the prospectors and speculators.

In northwest Washington, boomtowns often centered around logging. 150 years ago, Skagit County boasted a community created by wood of a different sort: log jams! Skagit City, located just below the point where the north and south forks of the Skagit River diverge, owed its fortunes in large part to these natural river blockades. And although the town went boom and bust within the span of just a couple of decades, it played a key role in the development of the area.

In northwest Washington, boomtowns often centered around logging. 150 years ago, Skagit County boasted a community created by wood of a different sort: log jams! Skagit City, located just below the point where the north and south forks of the Skagit River diverge, owed its fortunes in large part to these natural river blockades. And although the town went boom and bust within the span of just a couple of decades, it played a key role in the development of the area.

The Skagit City Boom

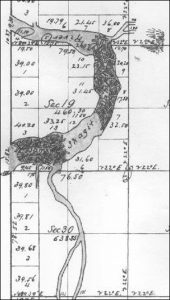

Jo Wolfe, director of the Skagit County Historical Museum, explains that, “White settlers began to take root on Fir Island in the 1860s.” Located between the forks of the Skagit River and Skagit Bay on Puget Sound, the triangular piece of land just under 10,000 acres was prime for farming. Skagit City was soon founded on the northeastern corner of the island.

The town served as a commerce center and gathering place for residents of Fir Island and for people starting to settle the Mount Vernon area. Skagit City featured churches and saloons, hotels and business establishments. A post office plus various fraternal organizations and cultural activities drew people in. A river ferry took passengers from bank to bank.

Log Jam Life

A 1876 article from the Washington Standard introducing the Skagit River to the rest of the state noted that, “The peculiar nature of the river is the Jam, about two miles above Skagit City.” This snippet understates the obstructions and impact they had on life in town. There were actually two immense log jams that meant, Jo says, “life and death” to the community. The older of the two, just below present-day Mount Vernon, was roughly a half mile long, and so dense it had trees 10- to 12-inches in diameter growing out of it. Reliable estimates pegged its age at around 100 years old. The second jam, about a half mile upriver from the first, was even larger. Both jams consisted of several layers of driftwood and debris 30-40 feet deep.

Since river traffic was effectively stopped at the lower jam, Skagit City grew rapidly. A steamship called once a month, and sternwheelers tied up at a wide riverbank to leave mail for locals and for points inland. Jo imagines the community “bustling with activity as people came out to meet the paddle wheelers.” Residents would have eagerly anticipated mail and news, along with deliveries of produce, dry goods and farm equipment they had ordered.

The log jams contributed to the atmosphere of the town as well. Otto Klement, one of the area’s first settlers, wrote in his memoirs that the lower jam: “Supported a forest growth scarcely distinguishable from that prevailing on the river’s banks. This forest rose and fell with the river.” The jam gave the impression that the river came to a “sudden end,” and was dense enough to act as a bridge. Otto also noted: “In times of flood, owing to the settling and shifting of the mass in the upper regions of the jam, a weird note of groaning was produced, not unlike that of a monster in pain, while sharp reports of breaking timber could be heard for miles around.”

Clearing the Jams by Hand

The pressure of commerce waiting to be conducted was not to be denied. Opening the river beyond Skagit City would mean expansion of logging operations in the area and transportation for coal that had been discovered in Hamilton. Roads were difficult to construct through the forest. Indeed, the only “road” worthy of the term had been built by Native Americans for hauling canoes around the lower jam.

Settlers petitioned the federal government for assistance, and when none was forthcoming locals took on the job of clearing the jams in February 1876. Using just hand tools such as saws, picks and axes, men tackled the lower jam first. They began cutting down the trees growing out of the debris, then worked on the surface of the jam. As logs were rolled into the river, more layers of driftwood would rise for removal. By September of 1876 much of the lower jam was gone.

Work on the upper jam began in May of 1877 and continued for two years before the river was navigable. Additional efforts finally cleared the river completely by 1879. Boats were able to travel up and dock in Mount Vernon and beyond. Supplies flowed east to fuel growth of towns like Sedro and Concrete while timber and coal traveled west.

The Open River Changed Everything

The men who worked so hard to clear the jams earned the gratitude of their communities, but not much else. In fact, most accounts have each one about $1,000 in debt by the end of the job as they lost time and tools to the jams and failed to harvest the bounty of useable logs they had imagined.

Skagit City was a casualty too. Once the river was no longer impassable, boats continued to call at the town but traveled east as well. Commerce dwindled, and erosion of the sandy bank where the sternwheelers tied up contributed to the town’s demise. By 1929 ferry service was discontinued, and what was left of Skagit City vanished as buildings were torn down or reclaimed by the river.

Jo Wolfe believes there may have been a move to relocate some of the town’s activity inland on Fir Island. Children attended as many as three different schoolhouses ruined by floods until a new school building was constructed on higher ground on Moore Road in 1902. Although it stands as a lone structure with most Skagit City residents relocating upstream or to established towns like Conway, Jo feels fortunate “that the building remains as a reminder of what was.”

How to Learn More

Unlike ghost towns that dot drier areas in the West, Skagit City is truly gone. You can walk the riverbank just below Mount Vernon to get an idea where it used to be—many residents and visitors have done just that and found a sandy bench that may well be the docking site for the old paddle wheelers.

Stopping by the schoolhouse on Moore Road can help you get a feel for Skagit City. The building boasts the original fir floor and decorative woodwork of its era, as well as photos and other information about the area. It’s the only historical building left near the location of Skagit City.

You can also visit the Skagit County Historical Museum in La Conner to find exhibits, maps and photos that bring life in the county—old and new—in focus. Check out the Skagit County website for directions and current hours.

Note: additional background material for this article came from the Skagit River Journal.