Out in the farmland west of Mount Vernon, Jonkheer Greenhouses occupies a unique spot in the $300 million agricultural scene in Skagit County. The company stands alone among the nearby flower and bulb producers; the crop here isn’t tulips or daffodils—hydrangeas are the stars of the show.

A first glance at Ted Jonkheer’s roots might suggest that he was destined to travel a familiar route for flower farmers immigrating from Europe to the Pacific Northwest. But over the course of decades in the field, Ted has evolved the business to meet changes in the market and his own vision of the kind of grower he wants to be.

Dutch Heritage

Ted’s father, Antone (Antoon, in Dutch), was born into a flower bulb family in the fertile farmland between Amsterdam and Rotterdam. Antone was the second youngest of 10 children: 8 daughters and 2 sons. The family name reflects European tradition, according to Ted. The oldest son is the duke; any boy who comes along later may be referred to as a “young heir,” or “Jonkheer.” As the children came of age, the older son took over the family business and Antone received a boat ticket. “Go sell some bulbs,” Ted’s grandfather told his dad.

Arriving in the U.S. in 1927, Antone landed a sponsor in Babylon, Long Island, who hailed from the same Dutch town as the Jonkheer family. Antone sold bulbs for Martin Spaargaarden, becoming quite successful traveling throughout the rust belt.

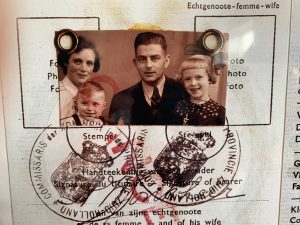

During these years, Antone bounced back and forth between Holland and the U.S. He married Ted’s mother, Petronella, and the couple had two children. Ted (Theodoor) was born in Holland in 1938. With war on the horizon in Europe, the family sailed across the Atlantic on the coal burning ship The Rotterdam to settle on Long Island in 1939.

West to Skagit County

Ted went to school in New York until he was 12 years old. By then, “everyone seemed to be moving west,” he recalls. His father had met another immigrant in the bulb business, Willem (Bill) Jansen, who said “I know a guy in Washington who might be interested in some help.” The Jonkheers relocated to Skagit County.

Ted graduated from Mount Vernon High School in 1956, while his father took on more clients and sold daffodils and iris across the country. Unlike Antone, Ted was interested in growing. He and his wife, Rita, a young woman from Sedro-Woolley whom he met at a picnic, bought farmland in 1963. While they raised a family of three girls, Ted raised daffodils, hyacinth and blooming branches. And tulips, of course.

For years, Ted sold flowers to wholesale and high-end florists all over the west. He specialized in forcing bulbs to bloom at times flowers were in demand but not in season—for tulips, this means winter. He remembers getting a call from a client he knew as “Uncle Ben” who wanted enough creamy yellow blooms for 100 tables at a large convention. “Imagine how many tulips that would be!” Ted laughs. He found a hybrid variety called Francoise that fit the bill and filled the order.

Changing with the Times

Specialty growing is not an easy pursuit. Forcing flowers like tulips means freezing and thawing at specific times and rates. It’s also expensive, considering labor, fuel, shipping and other costs. And timing is of the essence—you need to sell and ship the blooms right away.

Coupled with these growing challenges are changes in the marketplace. According to Petal Republic, while the U.S. is the biggest consumer of cut flowers, this country doesn’t even account for 1% of the world’s production. Increasingly, flowers sold here come from Latin America. In Ted’s eyes, tulips have become “a worldwide weed,” with Southern Hemisphere blooms available at the time he used to force his bulbs.

About 15 years ago, Ted decided to concentrate on growing hydrangeas for the wholesale trade. Unlike tulips that lose 15% of their value every day they travel, according to the BBC, “hydrangeas are like expensive wine,” Ted says. “They get better with age.” He explains that his five varieties change color over time, displaying soft to intense shades of cream, green, pink and blue. Some blooms show a hint of color at the edge of the petals, some creamy flowers have a tiny baby blue eye, some are a showy mix of pink and purple. As they age, the flowers tend to take on a green hue with another shade on the rim of the petals. “This antique look is popular,” Ted explains.

Jonkheer Greenhouses

Many home gardeners know that you can influence the color of hydrangeas with soil additives. To achieve his flowers’ spectacular colors, Ted grows the plants in containers and uses proprietary blends of additives based on aluminum sulfate. Three big greenhouses and four Quonset huts house the plants to protect them from freezing.

The blooms are harvested and stored in a classic red barn built in 1902, then shipped via truck along the West Coast or via air to other states. Adapting to current times includes maintaining “known shipper” status with the government and hosting FBI visitors ensuring Jonkheer Greenhouses is not involved in terrorism.

Working alongside just two employees who have been with him for more than 20 years and focusing on one floral crop suits Ted well. He’s not interested in the noise and crowds of agritourism or in selling flowers in busy places like Pike Place Market in Seattle (though he once did). But that doesn’t mean he’s without new ideas. “My next plan is a true purple,” Ted says. Not a deep shade of pink, not blue violet, he means “true purple.”

If you’re a hydrangea fan, watch the Jonkheer Greenhouses Facebook page and maybe you’ll spot it.