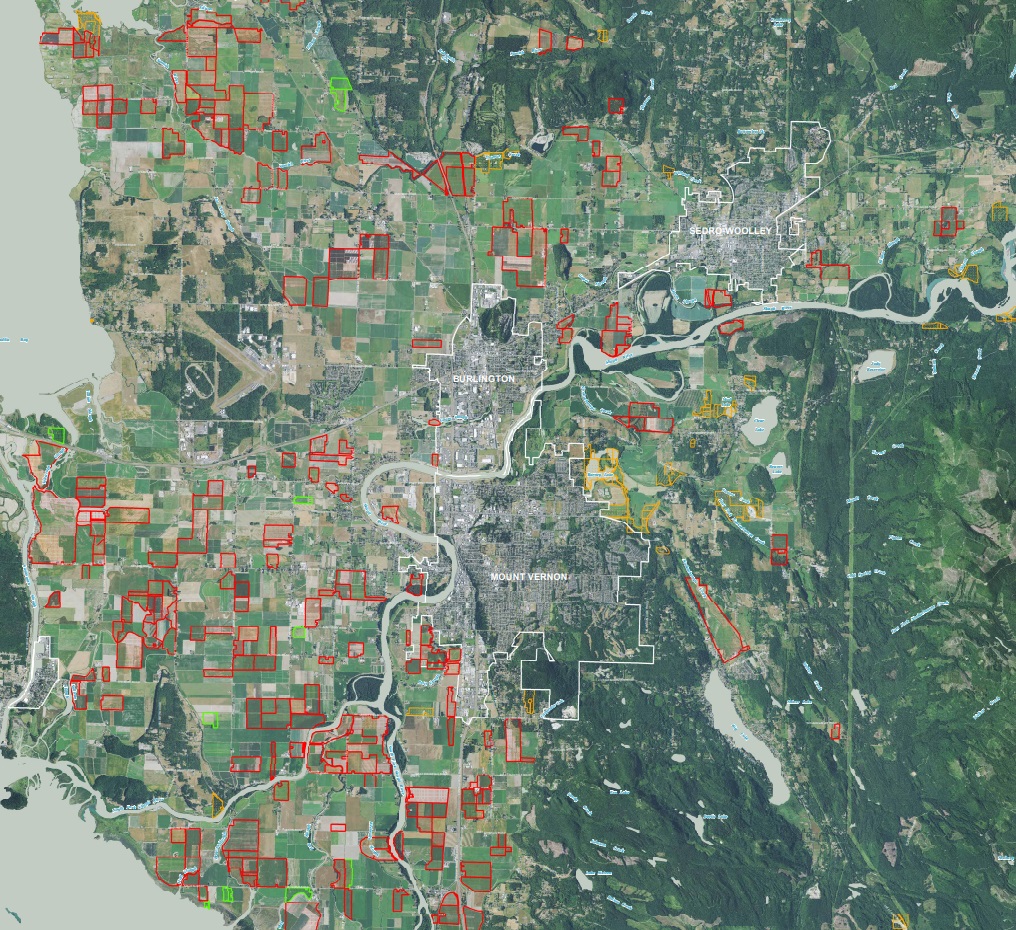

Skagit County is currently home to about 89,000 acres of zoned farmland, a bountiful spread of agriculture the area has long been renowned for. That acreage, however, is at constant risk of decreasing as development brings more and more people to Skagit Valley. Between 2012 and 2017, about 9,000 acres of Skagit County farmland disappeared, according to agricultural censuses. About 10,000 acres of farmland was lost in Whatcom County during the same timeframe. That’s where the Farmland Legacy Program comes in. Established in 1997 by the Skagit County Board of Commissioners, the Program uses taxpayer-collected county funds to pay landowners for placing conservation easements on their land, indefinitely keeping farmland from non-agricultural development.

Farmland Legacy Program Makes a Difference

To date, the program has protected more than 15,000 acres, with nearly 200 agricultural easements monitored annually. An average of 500 acres a year are being added to the program. If this pace continues, Skagit County will have 30% of its agricultural land protected by 2046.

Bank of the Pacific’s Scott DeGraw, a commercial banking officer who specializes in agricultural lending, is a longtime Skagit County resident and farmer. DeGraw is also the chair for the Farmland Legacy Program’s advisory board, comprised of seven citizen volunteers with a variety of backgrounds.

Over the years, DeGraw says they’ve gone from just making sure people knew what the Farmland Legacy Program was to refining it to benefit as many people as greatly as possible.

“It’s been a great program, and we’ve got some farmers out here who’ve used it multiple times and really helped preserve a lot of farmland,” he says. “They really see the benefit of that, and we appreciate their confidence in the program.”

Skagit County Agriculture: More than Growing Food

Sarah Stoner, agricultural lands coordinator for Skagit County, says protecting farmland is about more than just guaranteeing the production of food as a commodity, it’s also about helping prevent a wealth of land-related issues.

“Every time land is no longer being farmed, impervious surface and draining concerns arise,” she says. Every time a home is built in a flood plain, the county’s flood and emergency response issues increase. So far, 275 residential homes have been kept out of working farmland located in flood plains because of the Farmland Legacy Program.

“Farming becomes more difficult when farmland is fragmented by development,” Stoner says. “The existence of this program – and the incredible support it has from citizens paying into it, the commissioners, and the ag community – really underlines what the values are in Skagit County.”

With additional pressures upon existing farmland, which include aging farmer populations, water rights, salt water intrusion, changing weather patterns and placement of green energy methods like solar panels, the Farmland Legacy Program’s importance is only set to grow in coming decades.

Payments from the Farmland Legacy Program

For landowners participating in the Farmland Legacy Program, the size of payments is determined by the number of development rights a piece of land has, Stoner says.

Two appraisals of each piece of land are conducted: the first provides a best estimate of current value, while the second estimates the land’s worth post-easement. Essentially, the landowner is paid the difference between the two figures, for the perceived loss of value for not being developed.

With real estate prices still booming and farmland highly prized, Stoner says participants are currently getting to have their cake and eat it, too. Last year, the five pieces of Skagit County land conserved by the program netted the landowners $745,000 in total.

Both preservation and profit, DeGraw says, are powerful motivators.

“People want to use the program because they want to save farmland,” he says. “At the same time, they’re looking at their long-term plans – their family, their retirement – and going, ‘I still need to try and get as much money as I can out of this piece of property, how can you guys help me?’”

Getting Started in Farmland Legacy Program

Anyone interested in the program should first consider if their property is right for conservation. “Those seeking expansion of their facilities on conservation easement ground will need to consider how this would be impacted by the amount of impervious surface that easements allow. Overall, the program is fairly flexible in how it can be utilized,” Degraw says.

“Every piece of farmland is different,” says Stoner. “Even though it’s a really straightforward process – it’s basically a real estate transaction where landowners sign a deed of conservation easement – getting to that finished point can be different for everybody.”

Stoner says the process can start with a simple phone call to her, followed by additional meetings. The entire process timeline can also differ, but generally takes an average of eight months from application process to eventual payment.

“We have a steady source of funding, so we’re able to move quite quickly,” she says. “That’s pretty uncommon. Generally, a lot of other counties and a lot of other farmland protection and conservation agencies have to source third-party funds. And for every third-party you add into the mix, it will generally add another year to the process.”

While DeGraw’s farmland is not yet part of the Farmland Legacy Program, he is surrounded by land that already is. And when he looks at the future of his farm and his family, he knows that the willingness of Skagit County farmers today will make a positive difference in the future.

“My grandson is starting to farm with me, and down the road I want to be able to see this farmland preserved for him and future generations,” he says. “And the only way we’re going to do that is through the hard work of people in our community.”

Sponsored