In the early 20th century, reaching Whidbey Island from Skagit County – or anywhere else – meant relying on a boat, as there were no bridges or planes to take people on or off the state’s largest island. The Deception Pass Bridge would change all of that. Though it took several tries, the eventual construction allowed automobile and foot traffic between Island County and Fidalgo Island. This is the history of that now-iconic structure.

The Beginning of the Deception Pass Bridge

The naming of Deception Pass dates back to the spring of 1792, during the exploratory voyage of British Navy Captain George Vancouver.

Whidbey Island itself is named after Joseph Whidbey, master of the sloop of war known as the HMS Discovery, which Vancouver captained on his four-year circumnavigation of the globe. Whidbey and Vancouver originally thought the island was a peninsula, and were deceived by a deep, hard-to-navigate channel they had assumed was a bay.

By 1907, Washington was a state, but Whidbey Island still existed as a hard-to-reach place for most people. That year, a local mariner and legislator, Captain George Morse, created legislation calling for two bridges – one over Deception and another over Canoe Pass – to be built, finally connecting Fidalgo and Whidbey.

Site studies were conducted the following year, and Morse secured $20,000 in state funding for the bridge project. In 1909, Morse even showed off miniature models of it at Seattle’s Alaska-Yukon Exposition.

Unfortunately, the state legislature had other ideas, and re-appropriated the funds to other projects. In the meantime, inter-island ferry service took place, as did the construction of a convict camp and rock quarry.

The quarry, according to the Anacortes Museum & Maritime Heritage Center, was built into the rock bluffs of Canoe Pass, and was a steep, dangerous place to work. It operated from about 1909 through as late as 1914 before being dismantled in 1917.

In 1921, Nils Anderson also attempted to convince legislators that a bridge was of military necessity, as Whidbey’s Fort Casey needed a road to the mainland. His attempt was unconvincing.

In 1922, Congress designated the area around Deception Pass as a place for public recreation, heralding in the creation of Deception Pass State Park. There was still no to enjoy both sides on foot or by car, however.

From 1924 to 1935, hourly ferry service took place between 7:30 a.m. and 7:30 p.m. aboard the Deception Pass, a 68-ft long vessel. The route reportedly took only about five minutes, according to the book, “Ferryboats – A Legend on Puget Sound.”

The route was run by O.A. Olson and his wife Berte, who was allegedly the first woman to hold a ferry captain’s license in Washington State. Born in Norway in 1882, Berte became a loud advocate against a bridge that would ultimately end her livelihood as a ferry operator.

The Deception Pass Bridge Association

In 1928, the formation of the Deception Pass Bridge Association – which included Island and Skagit County representatives in the state legislature – made another push. The following year, the state legislature unanimously approved the construction of Deception Pass Bridge.

Berte, however, convinced Governor Roland Hartley to veto the bill. It did little to forestall the inevitable, though, as bridge legislation again passed in 1930. A different governor, Clarence Martin, did not issue a veto.

In 1933, a state bill passed that would have allowed the state’s parks committee to make Deception Pass a toll bridge if alternate funding through state bond sales fell through. In the end, tolls weren’t necessary, as the project was funded by the federal Public Works Administration and New Deal Washington Emergency Relief Administration, with additional funds provided by Skagit and Island counties. The total cost was $482,000 ($11.2 million today).

Bridge engineer O. R. Elwell was chosen to oversee the design, with Seattle’s Puget Construction Company hired to fabricate the bridge. The city’s Wallace Bridge and Structural Steel Company fabricated the steel, of which plenty was needed: 465 tons for the smaller bridge portion, and 1,130 tons for the larger section.

Construction began on August 6, 1934, with assistance from the nearest Civilian Conservation Corp camp. Workers used jackhammers and dynamite to break up thousands of yards of rock, constructed a concrete mixing plant on each side of the pass, and also created a cableway from Fidalgo to Pass for transporting materials.

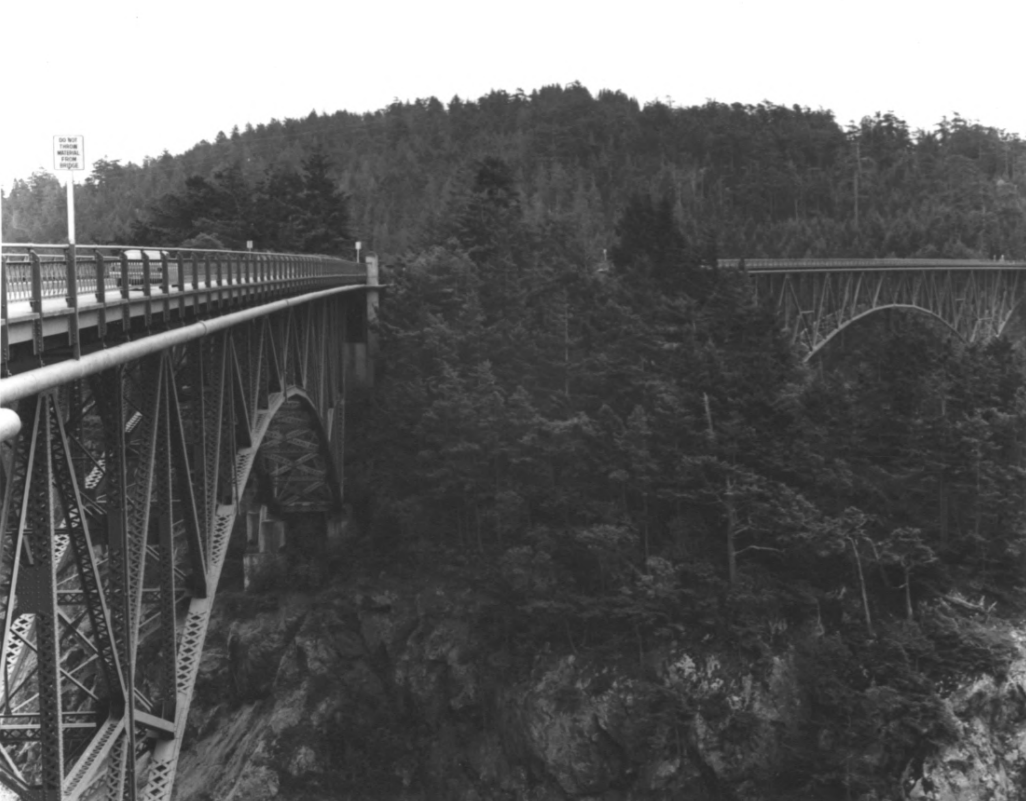

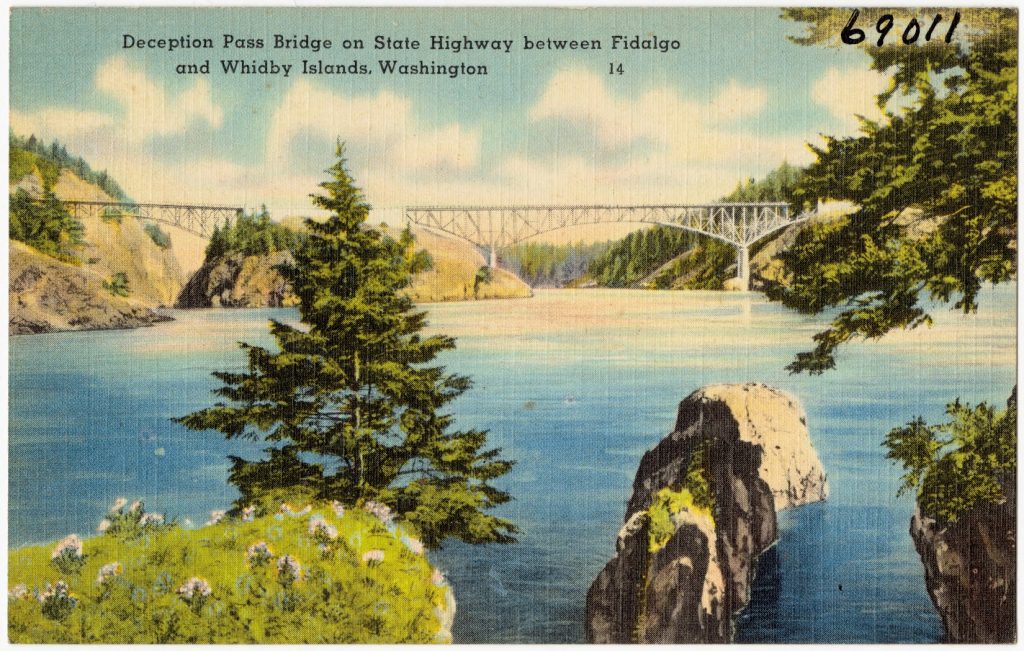

Between Fidalgo and Pass Islands, a 511-foot bridge consisting of a 350-foot arch and 3 T-beam approach spans was built. Between Pass and Whidbey Islands, the larger bridge – a 976-foot structure consisting of two 175-foot anchor spans, two 175-foot cantilever spans, a 200-foot suspended span and 4 concrete T-beam approach spans – took shape next, following the creation of a railroad track to transport materials to Pass Island.

The bridge’s center span was originally three inches too long on the summer day it was to be lowered into place. Engineer Paul Jarvis calculated that a 30-degree drop in temperature would counteract the heat-related expansion of the steel, however, and the next morning before dawn, the span fit perfectly into place when lowered.

Finally completed, the two bridges boasted a roadway 22 feet across, with 3 feet of sidewalk extending on either side.

Deception Pass Bridge Dedication and Legacy

On July 31, 1935, the Deception Pass Bridge was officially dedicated. Five thousand people attended the noon ceremony, which saw with Island County Representative Pearl Wanamaker christen the bridge with a bottle of sea water.

So many people attended, in fact, that the Governor Martin arrived late due to traffic. Festivities then moved to nearby Cranberry Lake, where families picnicked and listened to music by the Oak Harbor Drum and Bugle Corp, as well as the Mount Vernon High School band.

A reported 3,000 to 5,000 vehicles crossed the bridge during its first two Sundays of operation. Four decades later, Deception Pass vehicle estimates exceeded 1.5 million cars annually.

To this day, the bridge continues to be not only an architectural and engineering icon, but a true gateway and vista to the beauty of the area.